AGE OLD CRISIS Aotearoa’s ageing population is straining general medicine to breaking P.14 NOT PUBLIC INFORMATION The growth of private practice and lessons from Australia P.20 MILITARY GRADE MEDICINE Doctoring in the Defence Force P.24 The Magazine of the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists | ISSUE #136 | SEPTEMBER 2023

ISSUE #136 SEPTEMBER 2023

This magazine is published by the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists and distributed by post and email to union members.

Executive Director: Sarah Dalton

Magazine Editor: Andrew Chick Journalist: Matt Shand Designer: Twofold

Cover Image: Sezeryadigar/iStock

The Specialist is produced with the generous support of MAS.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Find our latest resources and information on the ASMS website asms.org.nz or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Also look out for our ASMS Direct email updates.

If you have any feedback on the magazine or contribution ideas, please get in touch at asms.org.nz

PREFER TO READ THE SPECIALIST ONLINE?

We have listened to your feedback and are aware that some members prefer not to receive hard copies of the magazine.

If you want to opt out of the hard copy, just email membership@asms.org.nz and we can let you know via email when the next issue is available to read online.

ISSN (Print) 1174-9261

ISSN (Online) 2324-2787

The Specialist is printed on Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified paper.

Proposed position for FSC logo and text. Please align to bottom of this margin.

PROFILE: DR PETER JANSEN

Quality and equity

The chief executive of Te Tohu Hauora, formally the Health Quality and Safety Commission (HQSC), describes the organisation he leads as a “critical friend” to the New Zealand health system.

PROFILE: MARKERITA POUTASI

Sea change for Pacific health

Improving health equity for Pacific peoples means rethinking Aotearoa New Zealand’s approach to Pacific communities, National Director of Pacific Health Markerita Poutasi says.

UPFRONT 02 Electing to do better 03 All the joy has gone 04 Paid union meetings energise members IN BRIEF 31 Regulating the Physician Associate profession 31 Nau mai, haere mai Te Mauri Taurite! 32 Lightening the load 32 Need to know 32 ASMS new staff member FEATURES 14 Age old crisis 18 A healthy culture 20 Not public information 22 Things that matter 24 Military grade medicine 28 In the interest of clarity 09

06

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 1

ELECTING TO DO BETTER

JULIAN VYAS, ASMS PRESIDENT

At the time of writing, we are balloting members about taking industrial action. Due to the ‘time lag’ between writing and publication, it is too hard for me to comment on strike action as, by the time you read this, the fight will have moved on.

Instead, I will look to October’s election. A review of the webpages of the five political parties in Parliament shows that none of them acknowledge the immediate senior dental and medical workforce crisis that exists.

Labour talks of increasing doctor numbers, National says they will open a third medical school, ACT will speed up registration processes, and the Greens talk of “meeting union demands for fair wages, pay parity and reasonable workload and conditions that support the well-being of health workers”.

Otherwise, there is nothing about the current situation. No party openly acknowledges how bad the current problems are and that, if left unchecked, they are an existential threat for the public health sector.

Our effectiveness at doing our jobs is predicated on our honesty. Our patients must be able to trust we are always truthful with them. Rudolph Virchow famously said, “Politics is nothing more than medicine on a grand scale.” I contend this aphorism not only relates to the goals to tackle personal and societal ills, but also relates to how politics should follow a ‘medical paradigm’ for sharing information.

Often doctors must give patients bad news about poor prognosis or treatment complications because patients have a right to be fully informed about their health. In the same way, New Zealanders should not be misled about their health system. Promises of fixes which ignore reality are nothing more than snake oil quackery.

At the same time, Te Whatu Ora must be open and transparent with its workforce, and not gloss over shortcomings. We have seen the continued ‘non-publication’ of the Pulse staff satisfaction survey. In addition, there have been two recent reviews of systemic failures at MidCentral and Southern districts. In both these reports, common findings have included recognition of a workplace culture neither accepting nor reacting to criticism. Rather, there exists a state of chronic denial of concerns, and disdain shown to those who raise them.

When senior clinicians are regularly subjected to this behaviour, it is no surprise that a state of suspicion and distrust develops between senior clinicians and our employer. Not only is it bad for us (and our managers) to work in such an environment, but sustained failure to recognise clinicians’ worries inevitably leads to poorer outcomes.

What we urgently need is a ‘reset’ of the current dysfunctional relationship between workers and employer in our health system. Te Mauri o Rongo, the proposed Health Charter should be an excellent starting point, but we still await its completion, and approval, by Government.

I realise properly embracing employer–employee collaboration may be difficult for Te Whatu Ora, but it seems patently obvious to me that Te Whatu Ora and the medical workforce both want the same outcome of improved patient care. The energy we expend to defend ourselves from poor employer practices could be far better spent on creating the means to improve patient outcomes.

We shall explore ideas to ‘reset the agenda’ at the annual conference in November. I encourage as many of you as possible to attend. It is through hearing your ideas and experiences that ASMS can best improve the terms and conditions we work under.

When senior clinicians are regularly subjected to this behaviour, it is no surprise that a state of suspicion and distrust develops between senior clinicians and our employer.”

– JULIAN VYAS

PAGE 2 THE SPECIALIST

ALL THE JOY HAS GONE

SARAH DALTON, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Last month ASMS launched our latest member survey focused on ‘other employment’. It’s part of our focus on workforce (and also on the public–private divide). It seeks to understand what influences some of you to leave Te Whatu Ora and explores some of the things that make it harder to work in our public hospitals. As well as providing statistical data, this survey also provides a rich vein of qualitative feedback that should help your employer and health funders understand how tough things are in public medicine.

As one surgeon put it: “I do not want to see people in clinic and tell them an operation would help but they can’t have one.”

Another SMO notes, “The RMO shortages are a nightmare and then all the work is left to us, and they argue about paying additional duties. All the joy has gone, there is nothing nice about coming to work anymore. I am actively looking for alternatives.”

Meanwhile, another SMO shared pictures of their non-clinical workspace. They are desperate not to lose the workspace, but equally concerned about the health and safety risks it poses.

This is the unhappy tale of working life in many New Zealand hospitals, right now.

No wonder increasing numbers of SMOs are fleeing over the road, or over the ditch… “Specialists are more valued in private. There is more recognition and appreciation of your skill, years of training and expertise, and this is reflected in how you are treated and dealt with … Being disrespected [in the public sector] while working hard, and to the detriment of yourself and your family, wears thin in the end,” says another member.

Yet another notes, “I work a shift with no registrar and the stress of having 20 [patients] a day leave without being seen is wearing me down. I’m thinking of just doing locums in Australia myself.”

What would help to keep SMOs in our public system, and what might attract some back?

According to our data, the top three items are remuneration, staffing levels, and resourcing. This list will be no surprise to you.

Mixed up in the remuneration debates are staffing levels and workload. Almost every service is short-staffed. Many, critically so. How do we attract the staff we so desperately need when workload is heavy and remuneration is comparatively poor, when RMOs are heading overseas with no intention to return, and when those who stay are rewarded with a pay cut in their first specialist post?

Recruitment is a dog’s breakfast, and the kind of sustained investment, supported by intelligent decision-making, that is needed to provide great secondary and tertiary hospital services seems a distant hope.

Meanwhile, we have a general election campaign underway, in which health is one of the political footballs being kicked around. We would like to see a maturing of political policymaking where some basics of health care – both investment and entitlements – are agreed. This would mean they’re not up for debate every three years. And maybe, just maybe, then you could focus on getting on with the specialist medical and dental work you were trained to do.

AN UNSATISFACTORY NON-CLINICAL WORKSPACE. SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 3

PAID UNION MEETINGS ENERGISE MEMBERS

Over 10 days in early August more than 1,500 doctors attended 29 paid union meetings across the country to hear in more detail about the bargaining of our collective agreement with Te Whatu Ora – what had taken place so far, our initial claim, Te Whatu Ora’s counter offers, and what action we might have to take to settle.

IN

GOOD DISCUSSION

ROTORUA. STANDING STRONG IN TARANAKI.

A CROWD GATHERS IN HAMILTON.

PAGE 4 THE SPECIALIST

HUTT VALLEY MEMBERS FLYING THE FLAG.

The mood of the meetings varied across the country but, in general, there was a widespread sense of being fed up with the continued overwork and undervaluing of senior doctors and dentists in New Zealand.

“We have got to send the message that if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys. You have to pay the appropriate salaries, or you will lose quality medical professionals,” a Tauranga member said. “We’re being asked to do more for less – this is the bigger issue than just pay. We need to be a bit more focused on what’s best for the health sector,” a Christchurch member said. While the question of pay parity with Australia came up at a number of meetings, there were mixed views.

“I can get 80 per cent more in Adelaide right now,” said one Christchurch member. “We must move quickly to get pay parity with Australia or no one will want to work with us.”

Other members were not convinced that kind of change was practical in one round of bargaining.

“Those people asking for pay parity with Australia are dreaming,” said a Rotorua member. “In Australia if they want to pay doctors more, they dig a hole in the desert, sell it to China and pay more.”

ASMS Executive Director Sarah Dalton says the paid union meetings generated some really good discussion. “The level of engagement from members was fantastic. It’s reaffirmed my belief in giving members every opportunity to discuss and debate meaty issues. And at this year’s Annual Conference we’re going to dedicate a substantive piece of the programme to let that happen and start the early work on developing claims for our next bargaining round.”

Dalton is equally convinced Te Whatu Ora still needs to bring more to the negotiations.

“Every employee in New Zealand deserves to have the value of their income maintained, especially when they are performing critical front-line tasks and being asked to cover as many staffing shortages as our members currently are.

“Te Whatu Ora seems happy for senior doctors and dentists to take a real-terms pay cut for the third year in a row – but we won’t stand for that.”

ASMS’s salary claim would deliver a (slightly better than) CPI increase to all members. This has several components: 3 per cent plus $4000 on the rates over a 12-month term; a new top step, and the removal of the bottom steps on both scales, and an extra increment for most members.

In response, Te Whatu Ora eventually tabled an offer with an 18-month term and an initial increase on rates of 3 per cent and $4000 but a delay in 12 months before delivering any additional step increment. On an annualised basis this equates to around a 4 per cent increase.

The ASMS National Executive proposed an indicative vote on the employer’s offer without recommendation. That offer was rejected 62 to 38 per cent on turnout of 68 per cent.

Members then took part in an official strike ballot and endorsed three possible days of strike action by 82 to 18 per cent with a turnout of 65 per cent.

SARAH DALTON AT THE AUCKLAND UNION MEETING.

SARAH DALTON AT THE AUCKLAND UNION MEETING.

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 5

A LARGE CROWD GATHERED AT AUCKLAND HOPSITAL.

PROFILE

We are the ridgepole that supports the health of New Zealand and the New Zealand health sector.”

PAGE 6 THE SPECIALIST

– DR PETER JANSEN

QUALITY AND EQUITY

MATT SHAND, JOURNALIST

The chief executive of Te Tohu Hauora, formally the Health Quality and Safety Commission (HQSC), describes the organisation he leads as a “critical friend” to the New Zealand health system.

“Te Tohu means ridgepole,” says Dr Peter Jansen (Ngāti Hinerangi, Ngāti Raukawa).

“We are the ridgepole that supports the health of New Zealand and the New Zealand health sector.

“We do not have legislative powers to tell people what to do. What we do is act as the critical friend who can monitor data, provide recommendations, and deliver programmes - all of which are aimed at improving the quality of services people in New Zealand can expect.”

The agency operates under the Pae Ora legislation and is responsible for assisting providers across the health and disability sector - both private and public - to improve safety and quality.

This includes work on advanced care planning, building leadership, infection prevention and control, medication safety and reviews of primary care and mortality.

Jansen hails from a background in rural general practice and says his affinity with the work of the Health Quality Safety Commission stems from efforts he undertook as a rural GP to create support networks across regions.

“We established a very strong, critical group of GPs who would meet and discuss what is happening across the different clinics,” he says.

“It was born out of the idea that, when you work collegially with others to make improvements, you get better results.

“It was at a time when after-hours and urgent-hour clinics were becoming a thing. I was placed in charge of the quality committee for Pro Care.”

A brush with cancer two decades ago saw him undergo intense chemotherapy and radiotherapy. That forced him to take a fresh look at what he was doing professionally and ask himself what he really wanted to focus on.

The answer was equity. Alongside his brother, Rawiri Jansen (now the Chief Medical Officer for Te Aka Whai Ora) he started Mauri Ora Associates, which has become a key provider of training and resources around cultural competency.

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 7

Dr Peter Jansen was appointed as the new chief executive of Te Tohu Hauora in April this year.

“The objective was to improve Māori equity through training the health workforce of Aotearoa,” he says.

Jansen moved on to work as a senior medical advisor to ACC and then also as Independent Chair of Medicines New Zealand, which he says has a strong grounding in quality, safety and oversight that he draws on in his current role at Te Tohu Hauora.

“Pharmaceutical medicine has a strong streak of quality and safety. When you think about randomised, controlled clinical trials, they are about improving the quality of care and comparing something against what we have now,” he says.

“All of that is invisible to the consumer - as it should be. The same goes for health care. A lot of what happens in health care happens the background - the training of the specialists and other clinical staff, for example.

“We have structures and tools to help understand what the patient experiences. But, when things go not so well and if harm occurs, how do we learn from that?”

HQSC has recently undergone an organisational review to assess its role in the health sector. The review identified a need for the organisation to come forward more and try to be more influential. One initiative in this area has been the development of data dashboards to help share the information they collect and make it more influential.

“Not only do we need to understand the problem, which we do through our data insights team, but we need to go further with all that information and take a more proactive approach to work with other health entities to say these are the real priorities and this is where we need to see change.

“Equity is the big one, especially health equity for Māori. The evidence is completely overwhelming. Māori get less care, less access to care and lesser outcomes. The evidence has been growing for decades and

now it is unmistakable. Now the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act spells it out.”

Jansen says SMOs play a key role in addressing health equity issues and should look to empower patients and families whenever possible.

“We need SMOs to model these behaviours. SMOs have huge experience and knowledge about how to translate difficult clinical concepts into understandable language.

“One of our programmes is about advanced care planning – “do you [the patient] want to be resuscitated? What matters to you and who can lead that?’. The people who can lead and model that experience are SMOs. SMOs are the leaders of our health system.”

Jansen thinks it is difficult to say exactly what success will look like in his new role. Instead he uses the example of a patient avoiding a fall to show the sort of improvements that can be achieved.

“We track data and, where we identify an issue, we develop programs to look at prevention,” he says.

“One area we have investigated is preventing falls at hospital. If you are a frail patient and you fall over and bust your head in the hospital, that is not a good thing. So we identified mechanisms that needed to be implemented, such as a falls assessment, that you can put in around that frail patient that prevent them falling.

“We have shown there has been a change in processes over time and we can calculate the number of people who have avoided a fracture and, therefore, the cost saved in the provision of extra care.

“We worked with local teams, we put the programmes into action and we published the findings. We will look for similar results for all our programmes.

“Because New Zealanders today expect to get value for money.”

Equity is the big one, especially health equity for Māori. The evidence is completely overwhelming. Māori get less care, less access to care and lesser outcomes. The evidence has been growing for decades and now it is unmistakable.”

– DR PETER JANSEN

PAGE 8 THE SPECIALIST

SEA CHANGE FOR PACIFIC HEALTH

PROFILE

When advice is being given in an acute space, in a hospital setting, a power dynamic can become even more pronounced.”

– MARKERITA POUTASI

PACIFIC HEALTH DIRECTOR – MARKERITA POUTASI

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 9

Improving health equity for Pacific peoples means rethinking Aotearoa New Zealand’s approach to Pacific communities, National Director of Pacific Health Markerita Poutasi says.

Pacific people make up about 9 per cent of New Zealand’s population, and 13 per cent of the people in Auckland. But only 2 per cent of doctors are from a Pacific background.

This disparity has contributed to a breakdown in connection between Pacific communities and medical professionals, according to Te Whatu Ora National Director of Pacific Health Markerita Poutasi, and she says this breakdown needs to be addressed.

Poutasi was previously the Chief of Strategy at Te Whatu Ora Te Toka Tumai Auckland and the Director of Pacific Health for the Northern Region Health Coordination Centre, where she led the regional Pacific health response to Covid-19.

“Pasifika relates to about seventeen different ethnicities and just as many languages,” she says.

“Right out of the gate we have a breakdown of communication, and that can lead to a lack of connection to the person sitting across from the patient.

“When advice is being given in an acute space, in a hospital setting, a power dynamic can become even more pronounced. It is about cultural safety.”

Pacific health statistics in New Zealand make for sobering reading.

Obesity rates show 71.3 per cent of the Pacific population are overweight. That contributes to the 11.1 per cent rate of diabetes across the population.

It is estimated that 29.5 per cent of Pacific peoples aged 45–64 and 53.1 per cent of Pacific peoples aged 65–74 have diabetes.

These statistics add up to a population that has a much lower life expectancy.

“There is a 5- to 6-year life expectancy gap,” Poutasi says. “Diabetes is the biggest killer in terms of life expectancy. It takes about an entire year off on its own.”

“It is for this reason our community has mandated us to take on this work and told us they want to see changes over the next two years.”

A Pacific health strategy – Te Mana Ola – has been established, and the National Director of Pacific Health has been included in the executive leadership team of Te Whatu Ora.

Te Mana Ola focuses on population health, prioritising disease prevention, seeking to understand the needs of Pacific peoples, ensuring there are timely services where they live, and growing Pacific health leadership and membership in the health workforce.

“Te Whatu Ora allows for us to have a view across the entire health spectrum,” Poutasi says.

“We can see what is happening in pathways to the hospital system. We can nudge and shift elements of community primary care where needed.”

“During the Covid-19 pandemic response the Pasifika community rallied behind each other, and behind providers of health care to support and vaccinate their communities.

“This Pasifika-led approach worked well to ensure patients and communities felt culturally safe and increased the engagement with health messages.”

Poutasi says there are new strategies to empower Pacific health providers and health care workers to perform their role.

“We have about 40 providers ready to go,” she said.

“In my role I can commission funding and services to enable them to do their role.

“We operate in a high-trust partnership with Pasifika primary health care and allow some of our smaller providers the ability to be equity leaders or champions.

“There are a lot of amazing Pacific providers, and we want to see them able to perform their work and retain their staff and workforce.

“The issues with retention [in the past] have been driven by the fact providers were often on shortterm contracts. By creating provider networks, we hope to alleviate the retention issues.”

Right out of the gate we have a breakdown of communication, and that can lead to a lack of connection to the person sitting across from the patient. When advice is being given in an acute space, in a hospital setting, a power dynamic can become even more pronounced. It is about cultural safety.”

– MARKERITA POUTASI

PAGE 10 THE SPECIALIST

Other developments that Poutasi points to are the implementation of the Pacific Health Senate, and the work of Pacific Health Navigators with families caught out by the current health care system.

“The Pacific Health Navigators improve pathways of care for families who have had long wait times for a first appointment,” she said.

“Often, there are more things to consider after clinicians have met with patients.

“Usually, the pathways are 1–2 weeks beyond the initial consultation and must take into account a variety of cultural factors to ensure care is met.”

Poutasi gives examples of situations where patients have taken leave from work for a procedure, then the appointment has been cancelled. “Often the family member knows they cannot take the time off again and so that operation might not be rescheduled or is delayed until that time off can be taken again,” Poutasi said. Families then miss out and have longer to wait to have issues resolved.

“Navigators can help people steer through these challenges. We want our providers and navigators to be at the front line of the equity issues in their services.”

Bolstering this effort are ‘earn to learn’ programmes to tackle the workforce shortage of Pacific health care professionals.

Poutasi also wants to see the expansion of targeted tertiary enrolment schemes such as the University of Auckland’s Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme and the University of Otago’s Te Kauae Parāoa policy to boost the number of Pacific doctors.

She says the Otago policy has already had an impact. “It’s fundamentally a solid Pacific programme and you can see students now rocking around and owning the university.

“It’s well run; they have a strategy and good clinical leadership, including Pacific doctors. What we now want is more funding and more placements as we know there will be benefits.”

PACIFIC HEALTH NAVIGATORS

Researching patients with long wait times on surgical lists created the rationale for the establishment of a new role at Te Whatu Ora in the form of Pacific Health Navigators.

The goal of the navigators is to help Pacific families work with the health system and increase understanding from specialists about the needs of Pacific patients.

“We walk alongside the patient and family to achieve health care outcomes,” Pacific Health Navigator Kaye Feyzabadi said.

“We advocate on behalf of patients and give them literacy of the health care system. We can coordinate better care and assist when there are multiple comorbidities that line up.”

The navigator staff all come from surgical nursing backgrounds and use that experience when dealing with patients.

“We often get referrals if a patient cannot be contacted or if they miss an appointment. Especially if there is a high risk of a cancer diagnosis,” Feyzabadi said.

“We are also trialling specialist appointments and try to see if there are any barriers before they get to the waiting list.”

The role was established after research was conducted into wait list times. It was found there were barriers preventing access to health care amongst Pacific communities.

“It is helpful for patients and specialists as well,” Feyzabadi says.

“The Pasifika model is family-centred, spiritual, and not individualistic. That is not something everybody knows and there can be disconnects when speaking to Pasifika patients that cause poorer health outcomes.

“It is a very rewarding role, especially when barriers are overcome.”

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 11

PAGE 12 THE SPECIALIST

A healthy culture Not public information Things that matter Military grade medicine In the interest of clarity 18 20 22 24 28 Age old crisis 14 SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 13

AGE OLD CRISIS

MATT SHAND, JOURNALIST

MATT SHAND, JOURNALIST

Aotearoa New Zealand’s ageing population is already straining our general medicine services to breaking point. And in the future New Zealanders will be getting older still. What is Te Whatu Ora doing in response?

PAGE 14 THE SPECIALIST

There is nowhere to take the patient so the news they were going to die, soon, had to be delivered in a Wellington Hospital corridor. Soon, the patient’s family would arrive to process the news and offer what comfort they can in the less-than private space.

“I am now routinely seeing all my new patients in the corridors of hospitals,” general medicine specialist David Tripp says. “We cannot do good doctoring in corridors. It feels like you are just hanging people out to dry.

“We see people on the worst day of their life, and we can only provide care for them in the corridors of the hospital.

“It turns us into people we do not really want to be, and every day I just feel like resigning. This is not what I went into medicine to do.”

Many hospitals around New Zealand are struggling to keep up with the influx of patients needing to be seen by the general medicine departments. The problem has long been identified. There are not enough doctors. There are too many patients, most with complex needs. And there are not enough facilities to house them now, let alone in the future.

These problems lead to ramped ambulances, bed block in wards, overcrowded emergency departments and dwindling morale amongst medical staff seeing it occur day after day.

As New Zealand ages, these issues are predicted to get worse.

Given people’s medical needs increase as they age, most people use the most public health resources in the last five years of their life. Projections show the number of people over 65 years old is about 800,000 now but will increase to 1.1 million by 2032 and up to 1.4 million by 2050.

“If nothing changes in the way we staff and size our hospitals, we are in for a real problem down the line,” Tripp says. “We’re being told to pedal faster, and it’s not going to work.”

“We are already in trouble. In Wellington the number of bed days each month for general medicine patients placed in other wards is now more than 950, as opposed to five years ago when that number was 350.

DAVID TRIPP.

AGEING POPULATION 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 0 Year Population 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2012 2020 2028 2036 2048 2060 2072 2008 2016 2024 2032 2044 2056 2068 2040 2052 2064 65+ 85+ SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 15

“Our 9am patient count is already higher than all previous years to date and almost higher than every winter peak, which has not even begun this year [at time of interview].

“Because we lack space, we also take up room in the emergency department. If we take up 10 of their beds it means they cannot run efficiently either. And the ED is just not structured for providing the same ongoing care as general medicine.”

Medical Director of Medical Services at Waikato Hospital Graham Mills says the birth and death rates are key to determining the size of medical workforce a country needs.

“Typically, in the last five years of a patient’s life is when they will place the biggest burden on health care services,” he says.

“We currently have about 38,000 deaths per year, and the bottom line is by 2050 that will almost double to 70,000 a year. Deaths will always occur, you cannot avoid this.

“That means in the world of general medicine, oncology and other end-oflife services, we will need to increase the number of nurses, doctors and buildings to cover that.

“Our health service planning does not appear to have taken account of the demographic change in the NZ population.”

AVERAGE 9 AM OCCUPANCY (%)

OUTLIERS – GEN MED BED DAYS ON OTHER WARDS

Mills says unless there is a radical change in the way New Zealand cares for people, the system will no longer cope.

Already the effects of general medicine overflow are affecting hospitals across the country. A presentation to Waikato Hospital management revealed the average wait for patients has increased from two and a half hours to almost four and half hours.

“At any given time on a Tuesday there are about 23 patients waiting in ED taking up space,” Mills says.

“We need a better solution to the current access block. There is an enormous amount of risk being concentrated in the ED ambulance bay and, as an organisation, we are not managing that risk well.

“This is going to cause patient harm and has already done so. The status quo seems to be that out-of-sight issues are out of mind. Pushing the problem back on ambulance staff is not a solution.”

Data shows over the past 15 years more and more patients over the age of 65 being discharged from Waikato Hospital.

“You can see the literal greying of the population and the health care system,” Mills said.

“We need a fundamental change in how governments budget health expenditure, which has to reflect our ageing population.”

New Zealand Chair of the Internal Medicine Society of Australia and New Zealand Michelle Downie has worked as a general physician across three hospitals in New Zealand.

“There are very few departments I am aware of that are unaffected by the global issues occurring with general medicine in terms of increasing patient numbers, increasing patient complexity, increasing age and increasing family expectations,” she says.

“This, combined with the reduced workforce, especially at the junior doctor level, puts a big strain on the system. Most departments are experiencing significant issues.”

Downie says the knock-on effect of ageing populations cannot be ignored and can no longer be blamed on the pandemic.

“These trends were emerging and present pre-pandemic,” she says. “I think the last few years a lot of things have been blamed on the pandemic. What Covid-19 did was exacerbate the problem for a system that already was not coping. We started to see the impact of the ageing population really take hold around 2015 to 2016.”

Downie says a key part of the problem is the lack of registrars, particularly in recent years, as part of the ongoing workforce shortage.

“There are not enough across the country. Everyone is carrying vacancies. What ends up happening then is the senior medical staff end up working as registrars. That means they must cancel appointments and back the system up more. For me, I would have to cancel my endocrinology and diabetes clinics so I could do those ward rounds.”

Downie says the crisis the health care system is in can no longer be ignored and the general public will soon be forced to radically change their expectations as workforce pressures worsen.

“There are many members of the public who will actively not take a patient home, and we see this a lot in general medicine,” Downie says.

“I have heard people say, ‘Oh it does not suit me to pick up my mother this day as we are painting the living room’.

“There is a public perception that people can just wait in hospital as long as they need, and this message of a crisis never gets through to the public and how dire things are with acute care.

“Nobody seems to be interested in the future because everybody is in crisis mode at the moment,” she says. “People in the health care system are 100 per cent aware the system is in crisis and the government continues to deny this.

1000 800 900 700 500 400 600 300 200 100 0 Jan 2017 Jan 2018 Jan 2019 Jan 2020 Jan 2021 Jan 2022 Jan 2023 Apr 2017 Apr 2018 Apr 2019 Apr 2020 Apr 2021 Apr 2022 Apr 2023 Jul 2017 Jul 2018 Jul 2019 Jul 2020 Jul 2021 Jul 2022 Jul 2023 Oct 2017 Oct 2018 Oct 2019 Oct 2020 Oct 2021 Oct 2022

160 120 140 100 60 40 80 20 0 Jan 2017 Jan 2018 Jan 2019 Jan 2020 Jan 2021 Jan 2022 Jan 2023 Apr 2017 Apr 2018 Apr 2019 Apr 2020 Apr 2021 Apr 2022 Apr 2023 Jul 2017 Jul 2018 Jul 2019 Jul 2020 Jul 2021 Jul 2022 Jul 2023 Oct 2017 Oct 2018 Oct 2019 Oct 2020 Oct 2021 Oct 2022

PAGE 16 THE SPECIALIST

“The issue may not become known until we admit the system is in a crisis and one that will absolutely get worse. This could result in people actively being unable to attend an emergency room or being forced out.”

Tripp says we are already close to the point of the system fully collapsing, which could result in closures to emergency departments as they are beyond capacity.

“It’s like a motorway. The cars will run smoothly if the numbers are kept at the level the road is built for. After that, you add one more car, and the traffic begins to exponentially back up until it causes gridlock.

“The wait times will only worsen and with that so too goes the level of care we can provide to more patients.

“We need more hospital capacity and more acceptance of the number of people requiring health care. In the absence of this, morale continues to slip away.

“I want to love my job – at the moment it’s pretty soul destroying. The naivety I see about the impact of our ageing population leaves me feeling pretty grim about the future.

ASMS Executive Director Sarah Dalton says the issues in general medicine are symptoms of systemic issues of underinvestment in the health care industry by governments.

Addressing workforce shortages is a key component to the ongoing MECA negotiations.

“We need to see greater investment in doctors to perform treatments and work in departments, such as general medicine,” she says.

“More doctors mean more treatment for patients and better working conditions for doctors. Stories like the issues in general medicine departments are becoming commonplace around the country.

“We are fighting for better pay and working conditions for doctors to ensure New Zealand is an attractive place to work to help get patients treated and doctors the colleagues they need to keep up with growing demand.”

Dalton says the ageing of New Zealand’s population reinforces the urgent need to pay doctors fairly.

“Doctors are a global commodity,” she says. “Te Whatu Ora must address the workforce shortfall now by taking steps, such as agreeing to fairer pay scales, to ensure our workforce is valued and continues to work in New Zealand.

“It is short-sighted to ignore the coming wave of increased demand driven by the ageing population and the flow-on bottlenecks that departments like general medicine will incur.”

Te Whatu Ora’s Chief People Officer Andrew Slater says it is “absolutely and categorically not acceptable” that hospitals are so crowded people must be treated in corridors or learn news they may die soon there.

“I think the ageing population and how we better support people in their community is a top priority for our organisation and that was identified in the reform. Specifically, we need to be working on what general medicine looks like in order to support that.”

Director, Transformation & Enablers, Commissioning at Te Whatu Ora Rachel Haggerty says the former DHBs were not good at looking 20 years ahead when it came to planning for changing populations.

“I think that is a fair comment,” she says.

“It’s a fair comment because people were trying to balance all sorts of demands and challenges across 20 balance sheets across the country.

“The short answer is we are aware of the issues caused by the ageing population. We are thinking about what beds we need and where those beds need to be. We are very conscious of the need to grow capacity, but we are also talking about what is the best model of care and service delivery for older people. The answer is not just more beds. This becomes more important as we see a massive increase in older populations.

“We have an increase in the population over 65 years old, but it is the population over 85 that is growing the fastest.

“When we talk about what facilities and hospitals we need, we need beds. The problem is building beds is slow with a long lead time. We are just doing nationwide capacity planning and service planning for our whole system, to look at where are our services are placed and how big they need to be to meet future demand.

“That will require a combination of hospital and home care support situations. Te Whatu Ora needs to work through how we continue to grow the strength of those services because demand on them will increase at the same rate.”

Plans are in place to undertake more aged care outside of hospitals and in the home.

“There is clear research that shows the best way to treat and rehabilitate older people is in their homes, but we do not have sufficient allied health and support staff available to assist people to get home sooner.

“Most of our conversation about older patients is how do we get them out of a bed because a bed is not always the best place to be. If they do not have a critical need, people decondition in a bed.”

There are facility replacement programmes and build programmes to address shortages in Tauranga, Hawke’s Bay, Palmerston North, Far North, Whangārei and Gisborne.

“The conditions of our facilities are hugely variable across the country,” Haggerty says.

“We do not want to just respond to failing buildings. We want to be proactive. Our workforce has a right to work in facilities that are fit for purpose and make it easier to do their job. And our communities deserve places of care that reflect what they need.”

But with nowhere to place patients, the issues of bottlenecking in emergency departments or general medicine wards will continue to be an issue.

Interim Director of Primary, Community and Rural Commissioning Emma Prestidge says the review of Te Whatu Ora’s aged care support services will look to adapt the model of care.

The review will assess the current state of aged care facilities and consider alternative funding models.

A $6 million pilot scheme has been established giving districts the power to pay for initiatives to facilitate discharges from hospitals to cover exceptional costs outside what aged residential care providers are expected to meet.

In response Tripp says he is tired of “linguistic gymnastics”.

“Of course we need to build community capacity – we see the results of current shortfall every day and of course we know patients need to get out of bed – I work on this every day,” he says.

“You can’t treat someone with severe pneumonia in the community.

“We have a critical and growing shortage of beds for patients who need them and are being harmed without them. Please listen to us.”

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 17

A HEALTHY CULTURE

Culturally appropriate services are central to respecting the rights of consumers, says Health and Disability Commissioner Morag McDowell.

The Health and Disability Commissioner says recently released decisions highlight the importance of culturally safe practice and the negative impacts on people where cultural consideration is lacking.

“HDC is committed to promoting and protecting the rights of everyone using health and disability services in Aotearoa New Zealand, and in doing so honouring our Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations,” said Morag McDowell.

Right 1(3) of the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights (the Code) states:

“Every consumer has the right to be provided with services that take into account the needs, values, and beliefs of different cultural, religious, social, and ethnic groups, including the needs, values, and beliefs of Māori.”

“It’s vital that people who experience poor outcomes in the health and disability system understand their consumer rights and their right to request feedback through HDC’s complaints process. We must close the gap in systemic disparities and inequity. We can only achieve

this by working together,” agreed HDC Kaitohu Matamua Māori/Director Māori, Ikimoke TamakiTakarei (Waikato, Tainui).

Ms McDowell says it is not sufficient for providers to have policies and protocols regarding cultural support pathways that are not actively and consistently used.

“These policies and protocols need to be put into practice if we are to improve peoples’ experiences and outcomes within the health system. It’s incumbent on providers to practise in a culturally safe manner, for example, by involving whānau in decision-making when appropriate. They must also be mindful of personal and institutional biases when people present for care, and when patients express their choices about the cultural support they require.”

She says three recent cases show a concerning need for education in this area.

“In one case a kaumātua’s cultural needs and beliefs were not upheld while he was an inpatient in a regional hospital for four weeks.”

We must close the gap in systemic disparities and inequity. We can only achieve this by working together.”

- MORAG MCDOWELL

PAGE 18 THE SPECIALIST

The Aged Care Commissioner, Carolyn Cooper concluded that consideration of the kaumātua’s cultural needs and appropriate options should have been made available from the time of his admission to hospital, to support the whānau to exercise control in caring for their koroua, in accordance with their tikanga and kaupapa — mana whakahaere.

In another case the mental health services provided to a 34-year old Cook Island Māori woman did not adequately take into account cultural considerations.

Despite the many opportunities for (then) DHB staff to consider culturally appropriate care, there was no evidence in the clinical records, or otherwise, that her cultural needs were assessed, or options for culturally safe care specific to her needs were discussed.

Finally a Māori man in his 30s died of a brain abscess arising from a rare, but known, complication of an ear infection. The man had presented to hospital five times over two months with recurring middle ear infection. During the presentations clinicians suspected him of being intoxicated with drugs (assumed from his former drug use) but failed to adequately assess him to determine if this was, in fact, the case.

“The Deputy Commissioner Vanessa Caldwell pointed out this failing raised the possibility of bias operating in relation to the man’s care. She was also concerned about the content and manner of a discussion with whānau,” said Ms McDowell.

The Medical Council’s statement on cultural safety was referenced in this decision – specifically; doctors should formulate treatment plans in partnership with patients that fit within their cultural contexts, and are

balanced by the need to follow the best clinical pathway and include the patient’s whānau in their healthcare when appropriate.

HDC has recommended the providers support restoration of mana through facilitating hui so whānau can express their mamae (pain), reflect on the experiences of whānau and how they navigate the health system, undertake self-learning for bias in healthcare, ensure options for cultural services are offered early rather than as an afterthought, and ensure their tikanga practice kaupapa aligns with the aspirations of Te Aka Whai Ora, with consideration of the elements of Pae Ora.

MORAG MCDOWELL IS THE HEALTH AND DISABILITY COMMISSIONER. SHE BEGAN HER TERM IN SEPTEMBER 2020.

The decisions referenced in this piece can be found here:

Assessment of needs and values vital to providing culturally appropriate care

www.hdc.org.nz/search-site?keywords=20HDC00354

Culturally safe care needs to be respected in assessment pathways

www.hdc.org.nz/decisions/search-decisions/2022/20hdc02383/

Assessment and action taken by an Emergency Department

www.hdc.org.nz/search-site?keywords=19HDC01783

MORAG MCDOWELL.

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 19

NOT PUBLIC INFORMATION

LYNDON KEENE, POLICY ADVISOR

ASMS’ 2022 ‘exit’ survey of members leaving their public sector employment during that year shows that while leaving for work overseas is a major reason for leaving (20.9 per cent), the proportion leaving to take up private practice (15.5 per cent) or to take up other non-public hospital employment (4.7 per cent) was equally important.

Results reported in Over the Edge: Findings of the 2022 Survey of the Future Intentions of Senior Doctors and Dentists found 42 per cent of over 1,600 respondents intend to reduce their hours in the public system, with many indicating a move to the private sector.

This year ASMS has followed up with two projects: First, a national survey of members to provide insight into the reasons behind doctors’ decisions to work part-time outside of the public system. Second, an investigation into trends in private health service use and the extent to which public hospital specialists are working part-time in the private system, using previously unpublished data from the New Zealand Health Survey and from the Medical Council’s Medical Workforce Surveys. The findings, which show movement from the public system to the private system on both counts, are being published in a new report called A Less Public Place.

Patients see the impact of this trend as soon as they seek a specialist appointment following referral from a GP.

The long wait

Nearly 44,000 people had been waiting more than four months for a first specialist assessment (FSA) in December 2022, an increase of 23 per cent since January of that year. While Covid lockdowns have had an impact, long waits were a feature of the system well before the pandemic, as the results of numerous Official Information Act requests published online by Te Whatu Ora show.

In 2019 patients could wait up to three months to see an oncologist in Waikato. At the same time, the average waiting time to see a cardiologist in Taranaki was four months, and the average waiting time to see an orthopaedic surgeon in Northland was more than six months.

These wait times are an outcome of long-standing specialist shortages. But not only that. Australia, for example, has many more specialists than Aotearoa New Zealand (estimated at well over 1,400 specialists per capita), yet long waits for FSAs in the public system are also common there. Detailed data is scant and inconsistently measured on both sides of the Tasman, but if anything the waiting times in general appear longer over there. In Victoria, for example, the time it takes for 90 per cent of patients to be seen is well over a year in at least 10 surgical and non-surgical specialties, and in some cases more than two

PAGE 20 THE SPECIALIST

As more light is being shed on New Zealand specialists’ decisions to move away from work in this country’s public health system, trends in Australia give an indication of where we might end up.

years. In Tasmania, patients with ‘semi-urgent’ conditions can often wait several years in some specialties.

Stephen Duckett, Health Programme Director at the Melbourne-based Grattan Institute, says that as well as the number of specialists available, it is “the hours they choose to work in public hospitals [that] affect the number of clinic appointments available”.

A study published in the Australian Health Review in 2017 involving eight specialties (orthopaedic surgery, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, cardiology, neurology, nephrology, gastroenterology, and rheumatology) found “a large majority of the time spent in patient care was provided in the private sector. For the surgical specialties studied, on average less than 30 per cent of clinical time was spent in the public sector.”

Proportionately, Australia has a much larger private health sector than Aotearoa New Zealand, but as our private health sector specialist workforce is growing at a higher rate than in the public sector, the experience in Australia serves as a warning about the consequences for access to the public system.

And long-standing specialist workforce shortages in Aotearoa New Zealand create an additional hurdle. As an example, the total (public and private) rheumatology specialist numbers are already well below the level recommended by the Royal College of Physicians UK, meaning access to those services is well below professionally accepted standards. For public services, those access standards fall further still as on average about a third of rheumatologists’ time is spent in the private sector.

As in Australia, much of the private sector work is concentrated in the surgical specialties.

Half of the orthopaedic surgeon workforce’s time is spent in private or other employment. But a range of other specialties are seeing increasing specialist workforce hours spent doing private work, according to previously unpublished data provided to ASMS by the Medical Council.

Psychiatry, for example, has seen a 61 per cent increase in the number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) psychiatrists working privately from 2019 to 2022 (from 52.5 FTE to 84.3 FTE). Put another way, of the total growth of the psychiatrist workforce over that period, 25.3 per cent were private FTEs. A further 8.2 per cent were in other non-public health service employment (government agencies, universities etc). On average, more than a quarter of psychiatrists’ time is now spent in the private sector or in other non-public health service employment.

The trend towards more private work in psychiatry is reinforced by the results of a recent national survey of ASMS members on the reasons behind decisions to work part-time outside of the public system. Thirty-four per cent of psychiatrist respondents said they were thinking about working part-time in other employment.

In other larger non-surgical specialties, diagnostic and interventional radiology specialist FTEs increased by 49 per cent in the private sector between 2019 and 2022, while obstetrics and gynaecology specialist FTEs grew by 28 per cent.

In the smaller specialties, private FTEs in cardiology, gastroenterology, neurology, rheumatology, radiation oncology, medical oncology and respiratory medicine, among others, all increased at a higher rate than in the public sector.

The small scale of the workforce means a shift from public to private services of just a few

specialists in any specialty or location can further reduce access to the public system. Seven radiation oncologist FTEs moving to the private system, as they did between 2019 and 2022, represents a 10 per cent loss to the public system when research predicts a large mismatch between the supply of radiation oncologists and demand for radiation therapy in the coming decade.

Why the shift?

In the new national survey of ASMS members, remuneration, workloads and clinical satisfaction were identified as the most important factors behind decisions to take up – or consider taking up – other non-public employment.

What’s the answer?

In Australia, fixing the long-wait problem is described as “straightforward” by Sydney medical researcher Professor Graeme Stewart, who called on the federal government to urgently boost funding to public hospitals so they can better resource outpatient specialist clinics and increase training positions.

Professor Gary Freed of Melbourne University’s Centre for Health Policy is of the same view, saying governments need to offer more effective incentives to public practice to counteract the higher remuneration and better conditions in private practice.

ASMS members’ perspectives on what public health system pull factors might influence their decision-making are available online at https://asms.org.nz/a-less-public-place/

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 21

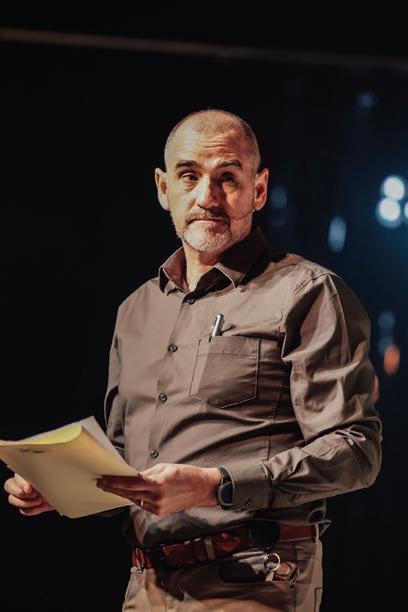

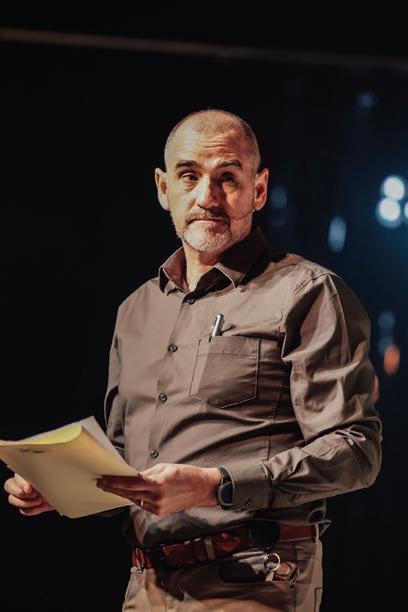

THINGS THAT MATTER

MATT SHAND, JOURNALIST

Satisfying his ‘fear of missing out’ has led to David Galler’s career as a doctor at Middlemore Hospital being adapted into a stage show at the ASB Waterfront Theatre.

The play, Things That Matter, was adapted from Galler’s best-selling memoir Things That Matter: Stories of Life and Death – based on his experiences in South Auckland as a health care professional.

“If you spend your life sitting on the couch, all you end up with is haemorrhoids and a DVT. But if you are willing to put yourself out there and push out of your comfort zone you never know where you might end up,” says Galler.

“Middlemore was my second home for a long time, and I spent more time at the hospital, especially in the first 10 years, than my actual home – which is a bit sad.

“I started writing quite a long time ago and had pieces published in New Zealand Doctor magazine. I found it useful to write down my feelings as a means of understanding things better for myself. I concentrated on and wrote

a lot about incidents, or incidences, at work and I found that underneath an issue I was interested in there were a whole lot of layers leading up to that event.”

The play, and book, are a homage to the South Auckland community Galler served, told through his eyes and the eyes of the patients he has treated.

“Someone asked if my book, and play, is a love letter to Middlemore Hospital and it is – and a love letter to the community,” he says.

“South Auckland is an incredibly culturally rich community with a great richness of culture and tradition. There are something like 140 languages spoken in the area alone. But, despite its richness, it is a community that has been predated upon by commercial interests, and the impact of that is profound.

“It is all connected, and someone will eventually come into the ICU and I would liken treatment to replacing broken panes of glass. They will come in and we will patch them up and send them out. They come back in a few months with three broken panes of glass and then, well, we never see them again because they ended up dying from that preventable disease.

ABOVE: IAN HUGHES AS DR RAFAL BECKMAN. BELOW: NICOLA KĀWANA AS CAROL.

DAVID GALLER: PLAYWRIGHT PAGE 22 THE SPECIALIST

“A lot of that is due to factors outside of their control. Shitty housing, low socioeconomic status, low-paid jobs, crap food, pokie machines, vape shops, cigarettes and other commercial interests profiting from their decline.”

The play explores these themes of interconnectedness from a health perspective.

“That interconnectedness between all things became a big interest to me. We often look at things as isolated, but in health there are a lot of interconnectivities. In health, particularly in South Auckland, there are commercial drivers to health, political drivers to health, and the process of writing allowed me to put these together in way I could explain it to myself.”

One example he uses is the impact of the removal of the housing subsidy in the 1990s. “That has been shown to be a major trigger for meningococcal B because the number of adults living in a house suddenly increased,” he said. “The housing subsidy was removed and families that lived in separate houses were forced to live together and, as a consequence of that, droplet-spread diseases had wider outbreaks.”

“Things happen to people, and it changes them forever and they never forget. Trauma has a marked and ongoing impact, whether it is trauma from illness or trauma of an assault. My parents were Polish Jews and my mother was an anxious person. They went through Auschwitz and that has ongoing impacts on future generations.”

It was when Galler decided to retire, which he “attempted twice but succeeded only once”, that he started to really focus on what the hospital represented to the community.

“I really started to pay attention to what was going on around me,” he says.

“I looked at my colleagues and the work they did and realised they are a really good bunch of people. I remember a kid being brought in, stabbed in the chest. He had a cardiac arrest in front of us and we intubated him – opened his chest up. The knife had gone into his heart and there was so much pressure around his heart it couldn’t pump. We put a finger and then a stitch into his heart and took him off to operating theatre. I just watched these teams of people save a life and I thought, these people are very good. They work incredibly hard; they are well trained and work well together.”

Galler assisted the actors in the play to prepare by taking them through Middlemore Hospital and helping them understand medical procedures and how the different parts of the hospital connect to help patients.

In the play he is represented as Dr Rafal Beckman instead of his real name.

“It was hard to let go, but I felt that if I used my real name I would be embedded in the entire truth, and some creative licence needed to be taken by the script writer,” he said.

“I read the script and thought they had done a very good job.”

Playwright Gary Henderson and director Anapela Polata‘ivao joined forces to produce the play.

Polata‘ivao says there’s never been a more relevant time to see the play, which addresses inequity and racism head on.

“There are some hard-hitting truths about racism and the impacts of the system on those living below the poverty line. It’s hard to hear these discussions, but they need to be heard and the play gives a voice to these issues, which ultimately affect us all,” she says.

ABOVE: DAVE GALLER’S BOOK. LEFT: THE CAST OF THINGS THAT MATTER.

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 23

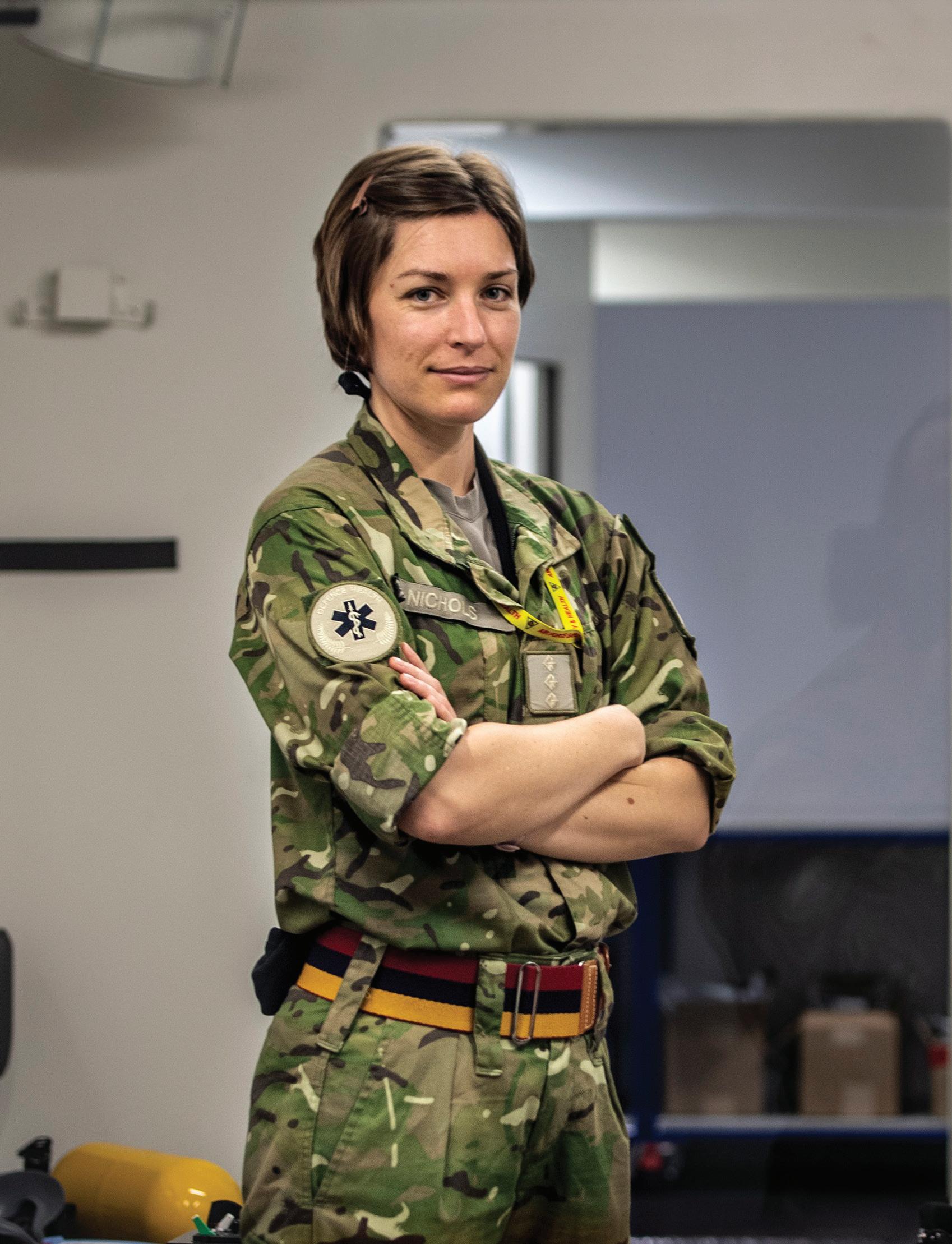

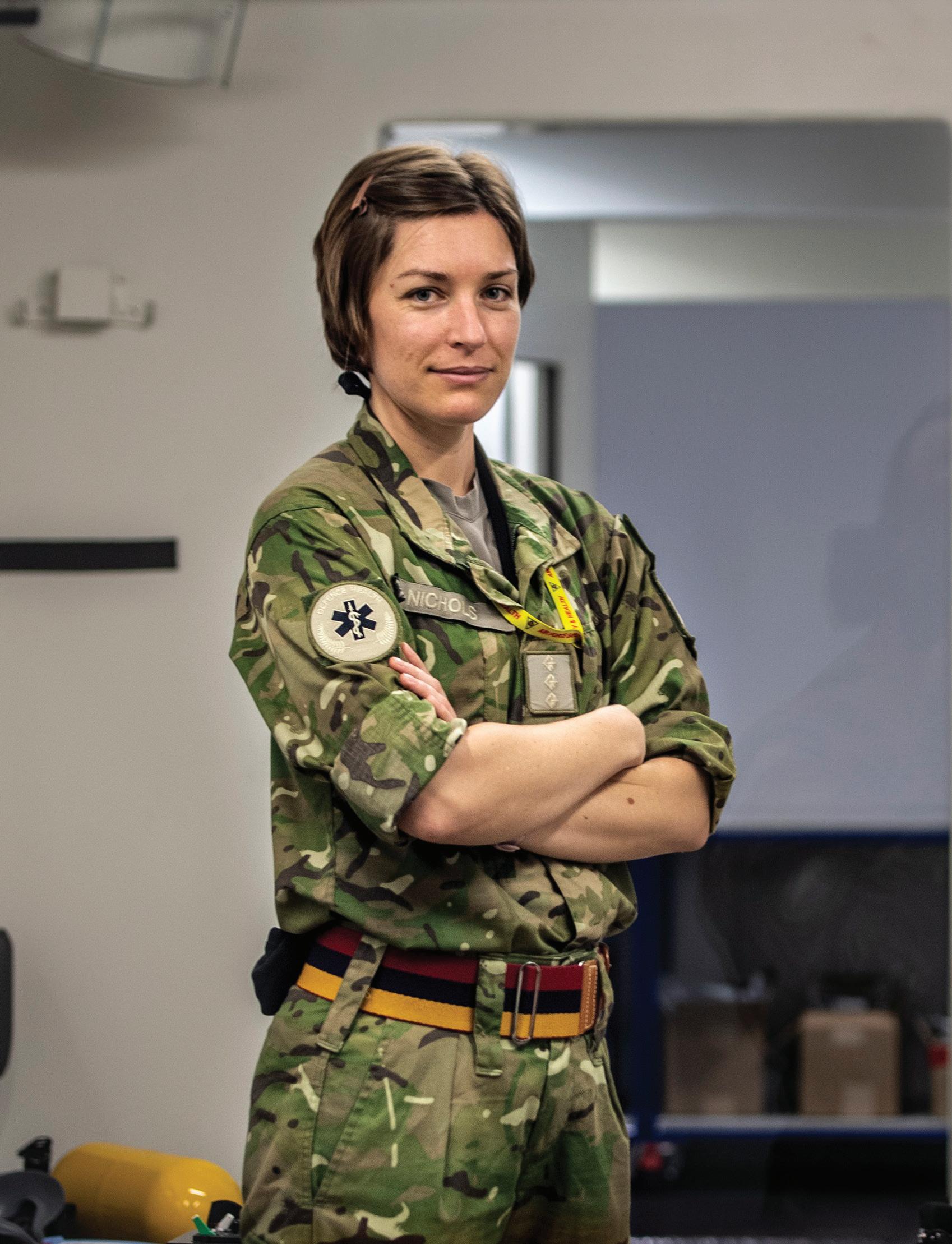

CAPTAIN KELSI NICHOLS.

CAPTAIN KELSI NICHOLS.

“It soon became apparent the working conditions in the general practice scope within defence are just so much nicer than out in the civilian world at the moment.”

PAGE 24 THE SPECIALIST

– CAPTAIN KELSI NICHOLS

MILITARY GRADE MEDICINE

MATT SHAND, JOURNALIST

Burned out is not a phrase Northland-based Lieutenant Surgeon Kim Rapson likes to use, but she admits it best describes how she was feeling before finding a new calling in the military.

Rapson was in her 50s when she decided to join the military. Her decision was based on needing a change after selling the general practice she had owned for 20 years.

“I wanted to be involved in something bigger than myself,” she said.

“Something international, and I feel that I wanted to be involved with a group that also worked for a greater calling.”

She found that change, and a renewed desire to practise medicine, when she enrolled in the New Zealand Defence Force as a medical officer.

Rapson’s typical week sees her providing medical care for military personnel at Devonport Navy Base in Auckland.

“What I love about working here is the ability to make a real change to patients without having the worry about their finances,” she said.

“The quality of care I can provide is usually far higher than I can provide in the community, and the actual care is not always available [in the community]. You can practise very good medicine in the military.

“In my previous job you always had to be mindful that the person may not be able to afford the treatment I offered them, and it puts them in a pickle. I love not having to worry about it.”

“If a woman needed an IUD, or an older person came in with a lesion, you have to discuss how that is going to cost them X number of hundreds of dollars.

“But I don’t have to think about that. I can say I think an IUD will be good, let’s do it next week.”

The job also sees Rapson travelling the oceans with the Navy to support crew and communities. In her relatively short time with the Navy she has travelled to Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

The challenge of practising medicine in different cultures, outside of the usual comfort zone of a hospital or clinic, is a welcome one for Rapson.

“It really pushes you to your limit,” she said.

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 25

Two doctors share their experience giving up civilian life for a career practising medicine as officers in the New Zealand Defence Force.

LIEUTENANT SURGEON KIM RAPSON.

“It is difficult to be plonked into a new culture or a new community and you must conduct yourself with the highest professionalism.

“It can be a dramatic change but rewarding.”

Aboard a Navy vessel, Rapson works as a specialist consultant to the ship’s medic staff and tackles high-level problems that could affect mission success. “Medics run the sickbay,” she said.

“We as medical officers must make some important decisions that have a big effect on a lot of people.

“It’s where my role comes to the fore. For example, do we need to send a person off the ship, do we send them back to New Zealand, and how do we manage this evolving situation?

“You have to focus on the individual but with a lens that we need this person to do a specific job and that needs to happen, and what is the higher aim of the mission to get it completed.

“I am a small cog in that, and a cog you never want to be activated because it means something is wrong, but the difference you can make is very real.”

Captain Kelsi Nichols decided early on that she wanted a career in the armed forces and discovered that decision could pay her way through medical school and open up a whole world.

A family connection revealed there was a strong career path for medical training in the New Zealand Defence Force.

“It was at a formative time for me as I was deciding what to do with my life,” she said.

“I learned there was a scheme that paid for some of the medical schooling and so once I got through the first couple of years of med school I got onto that scheme and the rest is history.”

A bonded scholarship became available to Nichols after she passed scrutiny by the Officers Selection Board. She learned this came with additional benefits such as earning the same salary as an officer cadet during her university study.

“It was a pleasant surprise for a medical student used to earning about $10,000 a year,” she said.

“In return, I had to get a B+ average and from postgrad year three onwards be bonded to the military to work for a certain number of years. For me, that was five years as I took the scholarship early.”

In between medical studies, Nichols undertook basic training. This involved learning to handle weapons, conduct fitness drills, learn about military law, and undertake leadership courses.

Medical officers also have specialist training similar to that undertaken by military officers.

“We had to learn things like how to assault a fortified position,” she said.

“Not that we would be doing that, but it was to understand what our infantry officers would be doing because we could be advising them within our specialist field as they do that process.”

Travel was a big part of the appeal of a career as a medical officer, as well as the shared sense of community from being part of a big family.

Once completed, she was able to travel the world practising medicine –including to Iraq.

“Travel was a big appealing factor for me,” she said. “Iraq was particularly memorable. That was a large-scale deployment that was almost combat aligned.

“I was there in a training capacity for the Iraqi security forces to assist them to do a better job fighting off ISIS. I was there providing health care within

PAGE 26 THE SPECIALIST

the small hospitals and providing primary health care as well. We were exposed to the threat of rockets coming into camps and other potential attacks. At the same time, it was a little town. You could go out for pizza, go dancing and head along to karaoke nights. It was such a different reality to a normal life.”

When not on deployment Nichols works in primary health care on her base. Working on base she will see a maximum of 12 patients each day, allowing her to focus on the needs of the patients better without time or monetary pressure.

“It soon became apparent the working conditions in the general practice scope within defence are just so much nicer than out in the civilian world at the moment,” she said.

“The pressures on us are completely different. We do not generate very many casualties in the New Zealand Defence Force, but we generate some very good work stories.”

“You can really make a difference the first time you see a patient because you have the time to do so,” she said. “You really build some trust with people on the base. You know you all share the same values.”

Nichols says the New Zealand Defence Force having GPs on call, available and free to access

for its staff shows the impact effective primary medicine can have on a population, if well managed.

“Part of that comes from not wanting to deploy people who are unable to perform their role or could become a liability,” she says.

“We do regular, proactive checks on our patients,” she said. “That allows us to achieve other health outcomes as well through preventive advice. That can include things like diet, sleep, mental health, and we can make sure any health outcomes are delivered.”

But there are challenges as well. The job does demand travel around New Zealand and on deployment overseas. “I’ve been away from home about 40 per cent of the working weeks this deployment round,” Nichols said. “It can be difficult to manage. We could always use more medical officers wanting to experience the benefits I have seen.

“The travel, the culture, the ability to practise good medicine, make meaningful appointments with patients and be part of a team with shared values are all good reasons to work with us.”

“The quality of care I can provide is usually far higher than I can provide in the community, and the actual care is not always available [in the community]. You can practise very good medicine in the military.”

– LIEUTENANT SURGEON KIM RAPSON

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 27

TOP: CAPTAIN NICHOLS AT WORK ON BASE. BOTTOM: CAPTAIN KELSI NICHOLS.

IN THE INTEREST OF CLARITY

DR ANDREW STACEY, MEDICOLEGAL CONSULTANT

Dr Andrew Stacey, a medicolegal consultant with MPS, considers managing conflicts of interest when specialists have a financial interest in medical facilities or equipment they are using or proposing to use in the treatment of a patient.

It is not uncommon for Specialists to hold a financial interest in medical facilities and equipment that they use to provide care to their patients. By way of example, Cardiologists routinely perform echocardiograms where they own the machinery, and Obstetricians and Gynaecologists routinely perform ultrasound scans for assessment and procedures. In such instances it is common practice to charge for their clinical expertise and additionally on-charge costs associated with the expense of the machine. Surgeons and other proceduralists may also have a shareholding in the private hospital/treatment facility where they operate or derive a financial benefit from recommending a particular intervention over another.

A number of organisations and regulatory bodies have expectations about how doctors should act in such situations.

The Medical Council expects that:

• Medical decision-making must always be free of commercial bias (or the appearance thereof) for or against any organisation, device, product, or service.

• Advice and treatment are based on the best available evidence.

• Doctors act in their patients’ best interests when making referrals and providing or arranging treatment or care.

• Doctors are honest and open in any financial dealings with patients and their whānau, employers, insurers and other organisations or individuals. When making recommendations or referrals, including to a particular facility, doctors should declare any relevant financial or commercial interest. If they have a conflict of interest, they should also ensure that the patient is aware of, and has access to, alternate sources of care.

• Doctors should be careful when referring a patient to a facility in which they, or someone they have a close relationship with, own or have a financial interest in retirement homes, surgical facilities, pharmacies, or other institutions where care or treatment is provided.

• If a conflict of interest is unavoidable, doctors must:

• advise their patient of the conflict and ensure that it does not adversely affect their clinical judgement;

• provide information about the facility to which the conflict relates, such as fees, incidental costs and wait times, so the patient can make a fully informed decision about their care;

• advise the patient of suitable alternative options;

• ensure that the patient does not feel pressured to receive care at a particular facility;

• make clear that the choice of facility is the patient’s and, whatever the patient chooses will have no adverse effect on the care provided by the doctor; and

• note the disclosure of the conflict in the patient’s medical notes.

• While doctors who are involved in the ownership, governance, shareholding, management, operation, or promotion of a healthrelated commercial organisation have a duty to the wider community, the organisation, and their colleagues, their first consideration must always be the interests and safety of patients.

Similar themes are expressed in the Medical Council’s standard for good medical practice:

• Doctors should be honest and open in any financial or commercial dealings with patients, employers, insurers or other organisations or individuals.

• Doctors should act in their patients’ best interests when making referrals and providing or arranging treatment or care. They must not allow any financial or commercial interests to affect the way they prescribe for, treat, or refer patients. In particular, they should not ask for or accept any inducement that may (or be perceived to) affect the way they prescribe for, treat, or refer patients. They should not put inappropriate pressure on patients to accept private treatment either.

PAGE 28 THE SPECIALIST

• If doctors have a conflict of interest, they must be open about the conflict, declaring their interest. They should also be prepared to exclude themselves from related decision making.

ACC has published position statements on the treatment of colleagues, and the treatment of family members and those close to you which also touch on this theme.

With reference to the treatment of colleagues, ACC notes that when determining whether treatment of colleagues should be funded by ACC it is important to also consider if treating them is ethical and reflects good clinical practice. When providing care this will entail considering whether there are any financial drivers for continuing the therapeutic relationship that could cloud clinical judgement, and when receiving care, whether there is any financial gain from seeking treatment from a colleague.

ACC, like the Medical Council, takes the position that doctors should avoid providing care to individuals close to them. In evaluating whether an individual falls into such a category, ACC invites doctors to consider a number of factors including whether the relationship between them and the individual is of such a nature that it could reasonably be expected to affect their professional and objective judgement. This includes situations where there is a perceived financial incentive between the doctor and the individual being treated, e.g., where either party has a financial interest in the practice.

The Medical Council expects transparency where a personal/business interest is present. This requires disclosure of any conflicts of interest. Commercial interests should be disclosed at the time of receiving a referral. This disclosure should conform with the requirements of paragraph 20 of the Medical Council’s ‘Statement on Doctors and health-related commercial organisations’, avoid providing non-specific information and needs to set out:

• The nature of the doctor’s interest (e.g., financial / shareholding).

• The specific entity they have an interest in. Any benefit or payment the doctor receives for the services provided (note this does not include payments or benefits related to the overall success of the organisation, such as dividend payments).

• That there are other options for care (which the doctor should describe or offer to describe).

While the provision of written information will likely help standardise the process, doctors should avoid treating this purely as a ‘box ticking exercise’. At the first consultation doctors should also discuss any conflicts with their patients. It should not be assumed that patients will not have a concern arising from the connection. The effect of disclosure should be that the patient is made aware that any conflicts the doctor may have will have no bearing on the care provided, and that decision making will be guided by the patient’s best interests. These disclosures should be documented.

Lastly, it is important to be aware of the provisions of the Commerce Act which prohibits restrictive trade practices. Doctors’ business arrangements should not substantially limit competition in the market, and contracts entered into for the purpose of (or having the likely effect of) substantially lessening competition in a market will be unenforceable. The Commerce Act also prohibits so called ‘cartel provisions’ - arrangements where two or businesses agree that they will not compete with each other and take steps amounting to price fixing, restriction of output, or allocating the persons and/or areas in which goods or services will be provided by or within.

There are significant penalties for doing so. The Commerce Act however does not prohibit collaborative activity (i.e. where a venture is not carried on for the dominant purpose of lessening competition). Doctors are advised to seek commercial legal advice prior to embarking on any business venture.

FURTHER READING

Medical Council of New Zealand

Doctors and health-related commercial organisations

www.mcnz.org.nz/assets/standards/Health-related-organisations. pdf

Good Medical Practice

www.mcnz.org.nz/our-standards/current-standards/goodmedical-practice

Providing care to yourself and those close to you

www.mcnz.org.nz/assets/standards/Statement-on-providingcare-to-yourself-and-those-close-to-you.pdf

ACC

ACC Position Statement: Treatment of colleagues

www.acc.co.nz/assets/provider/ps-treatment-colleagues.pdf

ACC Position Statement: Treatment of family members and those close to you

www.acc.co.nz/assets/provider/ps-treatment-family.pdf

SEPTEMBER 2023 PAGE 29

Surgeons and other proceduralists may also have a shareholding in the private hospital/ treatment facility where they operate or derive a financial benefit from recommending a particular intervention over another.”

Regulating the Physician Associate profession

Nau mai, haere mai Te Mauri Taurite!

Lightening the load

Need to know

ASMS new staff member

PAGE 30 THE SPECIALIST

IN BRIEF

NEWS FROM AROUND THE MOTU

REGULATING THE PHYSICIAN ASSOCIATE PROFESSION

Manatū Hauora | the Ministry of Health is currently consulting on the role of Physician Associates (PAs) and their professional regulation.